Burkina Faso: interview with Mariam Ouedraogo, journalist winner of the Bayeux Prize 2022

Mariam Ouedraogo is a journalist with the Burkinabe public daily Sidwaya, where she has worked since December 2013. She was awarded the Bayeux 2022 prize, in the written press category, for her series of reports “Axe Dablo-Kaya: la route de l’enfer des femmes déplacées internes” (Dablo-Kaya axis: the road to hell for internally displaced women). In this interview with Armel Hien, liaison expert of the Sahel Alliance in Burkina Faso, she shares her passion for journalism and her commitment to women victims of the crisis.

Why did you embark on a career in journalism, and what is the place of women in this profession?

I love this profession and I became interested in it very early. Even before I graduated from the Yadéga high school in Ouahigouya, I hosted two programmes on the radio station “Voix du paysan”. In 2011 I passed the entrance exam for journalism at ISTIC (Institut des Sciences et Techniques de l’Information et de la Communication). I studied there for two years, while doing internships at the newspaper Sidwaya. When I graduated, I was assigned as a journalist in this media.

I write for a media, but basically I do it for myself. When I work on a story, I make it my own until the story is published. Personally, I always manage to overcome the obstacles of the job, such as the lack of time to produce the stories.

Being a woman journalist is an asset to the job because we are more sensitive to certain topics than men. Most of my articles focus on the realities of women, children, the disabled, … The fact that we talk to each other makes it easier to talk, especially when we talk about issues like rape… We women journalists can understand, sympathise and console more…. As women journalists we are exposed to criticism too. People ask “will she be up to it; will she be able to do the job? But when I go out into the field to report, I don’t mean to brag in any way, but it’s difficult for men to produce the same quality of work.

What are your goals as a journalist in Burkina Faso today?

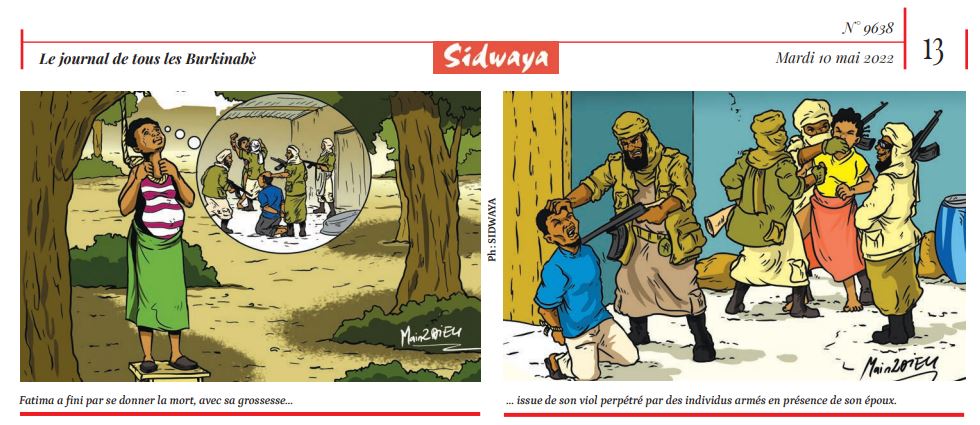

My goal is to continue to produce on a number of topics. The article that won the Bayeux Prize is part of a series of stories I started in 2020 when I wrote about the prostitution of internally displaced women. Subsequently, I produced another article entitled “Exaction by Armed Terrorist Groups: Unidentified Armed Individuals Rape Women to Death”. In this article I already announced that there were pregnancies. I went back to see what happened to these moms and babies… Those who decided to abort, what became of them? And those who were repudiated, have they been able to reintegrate their families or are they still marginalised by their community? I plan to continue writing this series of articles to see what happened to these children. Have they been taken into care? What is actually being done to help these survivors of terrorist hell?

How did your fieldwork for the series that won you the Bayeux Prize go?

I started this series of articles in December 2021. I went back to Kaya three times until March 2022, and I usually stayed for 8 to 9 days. I already had contacts there, which made it easier for me to work in the field. When you work on issues like these, you cannot turn a blind eye to the misery you encounter. Dealing with people in distress requires a lot of personal commitment, it has a certain cost and it is exhausting. I have a fragile health; I am taking a break currently in order to regain strength to pursue my work.

What have the Bayeux Prize and the reports following that prize changed in the way you work?

Before the Bayeux prize, I had already won 12 prizes but no media had granted me an interview! The Bayeux Prize revealed me to the world, the encouragement motivates me to carry on. The first articles I had to write on prostitution were very demanding. I even went on the streets to understand the reality of these women (but I didn’t go all the way!) and this affected me a lot, which made me sick. The doctors diagnosed me with vicarious trauma, which is a transfer of the victims’ suffering. I am experiencing the same thing as them without being directly affected. It’s a terrible shock, I didn’t know how to step back, maybe because I’m a woman. I put myself in their shoes and had to stop working for almost a year. In 2021 I did not write any article, on the doctor’s recommendation I went to Côte d’Ivoire for treatment, because my malaise had turned into asthma. Since then I have been living on borrowed time, which means that from one moment to the next I can have an attack when reporting. When I returned from Côte d’Ivoire in November 2021, I decided to go back into the field and publish the articles that were awarded the Bayeux Prize. The encouragement I have received makes me think that this is not the time to stop.

What is your perception of the crisis in Burkina Faso ?

It is sad for a country to be attacked from all sides, and most often by its own people. There are deaths, displaced people, families being torn apart, it has upset the order. We are no longer living; we are at war. I focused my reports on the Centre-North region. I would have liked to cover other regions such as the East (Fada) but accessibility is a challenge. It is easier to get to Kaya discreetly than to come to Fada. And the state of the road is problematic. But the realities are the same everywhere, six regions are severely affected by the crisis, these regions are experiencing the same attacks with the same intensity, there are displacements of populations followed by sequestrations as well as rapes and abductions. So these populations suffer the same consequences from the terrorists: the men are killed, the women are raped. If you are raped, and left with a child resulting from the rape, you don’t live because you will be living on the edge of society…

What message would you like to send to the world and to the international community in particular?

When there are attacks, there are countries and structures that condemn. We ask the international community to support Burkina Faso beyond condemnation, because the violence is gradually threatening to ignite the sub-region. Real solidarity is needed. We share borders, cultures, these are the same communities, so we must not fight in isolation. As far as the international community is concerned, it is necessary to provide substantial aid. Conflicts weaken states, but beyond the state apparatus, there are people who suffer, there are deaths, while our country needs all its sons and daughters to develop…

There is a proverb in Burkina that says that if your neighbour’s house is burning, you must go and help him because the fire can also take hold in your house. We must not wait; we can always anticipate. From the outside, countries and institutions can see our weaknesses, in terms of military strategies and especially in terms of taking charge. I see so many NGOs and actors working in the field of gender-based violence (GBV). But I am under the impression that there is no synergy of actions, each structure works on its own… and consequently the support is not efficient. I have spoken to many internally displaced women who have been raped and have never received any help. Some have even been forced to prostitute themselves in order to survive, even though there are funds circulating and being allocated to structures that are supposed to help them… And we must also go beyond donations of food and clothing because these people are affected for life. They need psychological care because many have suicidal thoughts. In addition, many children born of rape do not yet have a birth certificate, how will these children grow up without this document?

What do you think are the priority actions that should be carried out for the people?

Ideally, we should work to bring them back home. But for the moment, as the areas are still under terrorist control, it is difficult. Aid must be really consistent. A reintegration component with micro-projects and income-generating activities (IGAs) must be put in place, as well as psychological support and support for children. Many children, including orphans, are no longer attending school. There is also a resurgence of child marriages, with people being so overwhelmed that some get rid of their girls by giving them away in forced marriages…

Another important issue: emphasising the prevention of the transmission of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs), a phenomenon that will explode with what I saw in Kaya. Prostitution is taking place without protection. A project study showed that there were already many cases of new HIV infections in several areas where there are IDPs. So imagine that in two, three, four, five years, the data on HIV, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) will explode…. We can already anticipate this at the level of displaced populations and host populations. We need to review awareness raising, organise screening, and focus on identifying STD cases. A specific register could be set up (in social welfare or health facilities) for women who are victims of gender-based violence (GBV) so that these entities do not lose sight of these victims and that professionals can provide them with the best possible support, without leaving anyone behind..

Read the series of reports (in French) by Mariam Ouedraogo “Axe Dablo-Kaya: la route de l’enfer des femmes déplacées internes” in Sidwaya.

To go further

AFD is sponsoring the people’s award as a partner of the Bayeux Calvados-Normandy War Correspondents’ Prize for the 9th consecutive year.

A round table was organized during the 2022 edition on the humanitarian and geopolitical consequences of the war in Ukraine on Africa. Jean-Bertrand Mothes, head of AFD’s Fragilities, Crises & Conflicts Division, discussed with Dr. Comfort ERO, president of the International Crisis Group, Frédéric Joli, spokesman for France of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Ksenia Bolchakova, film director.

Since 2016, AFD has had a mandate to consolidate peace in fragile areas where it operates before, during and after crises. In order to provide a response to local populations, France has set up an adapted financing tool: the Minka Peace and Resilience Fund. Over the past 5 years, 863 million euros have been committed by Minka, half of which is dedicated to the Sahel. In this mission, the situation of women and girls is a priority: 90% of the financing committed by the Fund is devoted to them, i.e. more than half a billion euros. These results make Minka a pioneering fund for the implementation of the French action plan “Women, Peace & Security” 2021-2025.